Sri Lanka is a fertile tropical island in the South Asian region. The country’s climate, the healthiness of soil, and the availability of water have made agriculture, as one of the dominant sectors in its economy. Approximately 7% of its GDP and over 25% of jobs come from the agricultural sector. Rice is the dominant form of cultivation. The island nation is also known for plantation agriculture as well as abundant fruits and vegetables. Over 80% of the rural communities depend on the agriculture sector even today. Despite climate variability and its impacts to the sector, the local community heavily relies on cultivation of rice.

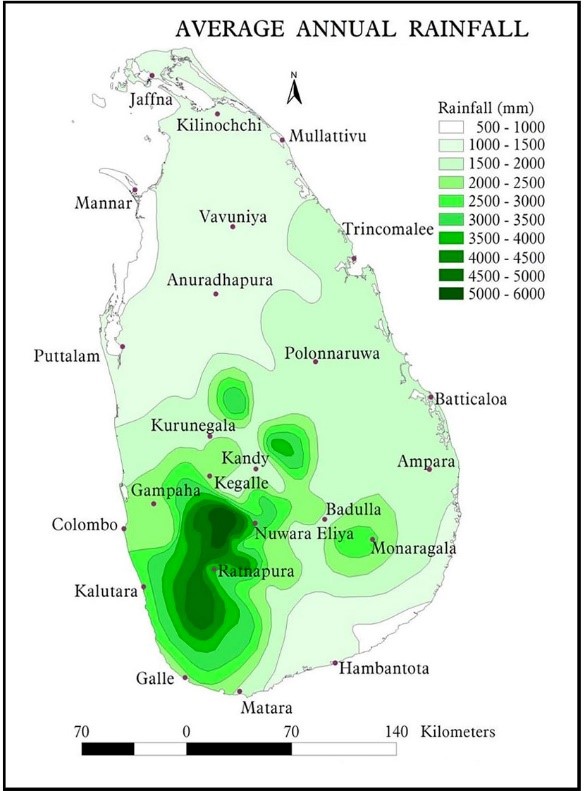

Sri Lanka is divided into three climatic zones on the basis of annual rainfall received in each zone. They are differentiated as dry, intermediate, and wet. The country experiences high seasonal and spatial variations in rainfall due to the monsoonal climatic pattern. The mean annual rainfall varies from, below 900 mm in the driest parts (southeastern and northwestern) to over 5000 mm in the wettest parts (western slopes of the central highlands).

The country receives its annual rainfall in four distinct seasons, influenced by the two monsoons. Those are:

- First inter-monsoon season (March – April)

- Southwest monsoon (May- September)

- Second inter monsoon (October- November)

- Northeast monsoon season (December- February)

Based on the rainfall and other associated climatic parameters, there are two main cropping seasons: “Maha” (Major) season from October to March and “Yala” (Minor) season from April to September. In general, the rural community cultivates rice during both Maha and Yala Seasons, disregarding the difficulties caused by climate change.

Annual rainfall received from these monsoons amount to about 130 billion cubic meters of water and approximately 40% of it runs-off. Out of this 40%, about 35% is used for irrigation and generation of hydro-power and the balance, which is the overwhelming majority of the run-off water escapes to the sea. Thus, nearly 26 billion cubic meters of water is wasted.

Understanding this phenomenon ‘island’s water balance’, our forefathers had depended on rainwater and had cultivated large extents of lands by constructing reservoirs and tanks in the Dry Zone of the country. For example – starting from Kind Abhaya in 3rd century B.C., Kings of the country constructed major storage reservoirs to arrest the run-off water thereby obstructing run-off to the sea. These were then used for agriculture, predominantly paddy in the driest parts of the country. However, these major reservoirs were not sufficient to cater to the increased water demand for agriculture due to the growth of the population. As a result, a network of small tanks was constructed in various time periods. This is currently known as village irrigation systems. They promote efficient water management and agriculture practices. These were used to irrigate the low-lying plains of the Dry and Intermediate zones, using micro watershed management approach commonly referred to as the tank cascade systems.

These were constructed as part of an agro-ecological system, that increased the productivity of the area, while also improving the eco-system benefitting the locals. Traditional water management in these systems is also based on principles of integrated water management, recognizing the multiple uses of water; irrigation mostly paddy, augmentation of the groundwater table, and also replenishment of local wells which are particularly important during the protracted dry seasons. It traps silt to minimize the siltation of village irrigation tanks, for livestock, and wildlife through a forest tank constructed above the village tanks, etc. However, with time and with influences of political and economic ideologies that the country experienced during colonial period, these vital infrastructures and associated eco-systems have been neglected for many centuries. Despite disuse and malfunctioning, these cascade systems and village irrigation systems continue to provide a lifeline for the Dry Zone communities, often being the only source of water.

The challenges of the dry and intermediate zones are getting worse, as the increasing trend in negative climate effects is expected to continue and get more severe. Analysis of climate models for future projections of rainfall shows that dry and intermediate zones will become dryer during the main rainfall seasons, although the annual rainfall would continue to increase. Over half of the people living in this region engage in farming or in employment related to farming. Therefore, the lives and livelihoods of these rural agricultural communities will be highly sensitive to these climate variations. Considering the present irrigation and agriculture scenario, the majority of the districts in the Dry Zone will face severe seasonal or year-round water-scarcity. On the other hand, women and youth in these areas are more vulnerable to climate change as the health of the family members and the household water availability depend on them. This also affects their household food security, which can be aggravated during extreme climate events.

As the irrigation demand is high in the dry zone it can also increase the total water demand of the people living in these areas. In view of that, it has been deemed vital to assess the present situation, to meet the future food demand and water demand in the dry zone. The districts, such as, Puttlam, Kurunegala, Anuradhapura, Polonnnaruwa, Mannar, Vavvuniya, and Trincomalee would mainly face problems in meeting future water demands.

Lack of a comprehensive and strategic approach backed by appropriate policies to ensure water availability in at-risk areas, prevents arriving at sustainable solutions. In this context, Ministry of Mahaweli Development and Environment with the technical assistance of UNDP, has implemented a seven-year project named The Climate Resilient Integrated Water Management Project (CRIWMP) to address issues in water availability and agricultural production in the Dry Zone. The National Water Supply & Drainage Board, being one of the responsible parties to the Project, plays a crucial role in advising the project on groundwater and drinking water management in the selected rural areas and assists the project to execute a systematic plan to provide year-round access to safe and reliable water supply to project beneficiaries.

The CRIWMP targets poor and vulnerable households in three river basins: the Malwathu, Mi, and Yan (rivers) which flow through the northern part of the Dry Zone. These river basins are among the most vulnerable to the variations of the climate and are located in areas where there is a high presence of village irrigation systems and cascade systems on which poor and vulnerable farming populations depend on, for their living. Thus, it intends to enhance dry zone water security and agricultural productivity covering Anuradhapura, Vavuniya, Kurunegala, Puttlam, and Trincomalee Districts.

The specific objective of the project is to achieve water management through an integrated approach through the following outputs:

- Improve irrigation by introducing climate-resilient agricultural practices.

- Improve access to potable water by enhancing community-managed drinking water infrastructure.

- Protect farmers and vulnerable groups from climate-related impacts by strengthening early warning systems and climate advisories.

With a view to improving the community-managed drinking water infrastructure, water-stressed areas have been identified to form rural community water supply schemes in the project districts. The CRIWMP Project will advance climate-resilient water supply and promote climate change adaptation in the drinking water sector to minimize the impacts of climate change.